What is EGS?

Equine Grass Sickness is a disease of horses, ponies and donkeys in which nervous system damage occurs. Gut paralysis is one of the major signs. It is almost always seen in horses which are grazing and rarely occurs in horses with only access to hay and not grass.

Some areas of the UK have a higher incidence of the disease particularly Scotland and the east of England. The disease generally peaks between the months of April to July and a small peak can occur in Autumn.

Can any horse contract EGS?

Younger horses especially those 2-7 years old seem to be more susceptible to the disease. Mare, geldings and stallions are all equally affected as are horses of different breeds. Generally horses over 10 years of age seem to be rarely affected and there is presumed partial immunity to the causative agent. Horses in good to fat body condition also seem to be more commonly affected. Stress, moving premises/field and certain weather conditions also predispose to EGS developing.

What causes EGS?

The general theory is that a bacterial toxin (Clostridium botulinum) found in pasture (or occasionally hay) is responsible. The bacteria produces a toxin which is absorbed by the intestines and exerts its effect on the nervous system.

What are the signs of EGS?

EGS occurs in three main forms: acute, subacute and chronic, however we see considerable overlap of these forms in some horses. The main clinical signs we see relate to paralysis of the gastrointestinal tract from the oesophagus to the rectum.

- Acute: Horses with acute EGS may be found dead or usually require to be put to sleep within two days of signs becoming apparent. Severe gut malfunction leads to signs of severe colic including rolling, pawing and flank-watching. Drooling of saliva and difficulty in swallowing is also seen. Spontaneous reflux, where digestive fluids build up in the stomach and then start to drain through the nostrils can be seen and inaction of the large colon (constipation) can also be seen. Many horses will have patchy sweating and muscle tremors are also common

- Subacute: Signs are similar to acute cases but are less severe. Accumulation of fluid in the stomach is rare, but weight loss and colic are often seen. Small amounts of food may be eaten; however, many of these cases will die or need to be put to sleep within one week

- Chronic: The signs start more slowly and weight loss (which can be sudden and extreme) or intermittent colic are usually the signs seen. Some horses may also have difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) and show a poor appetite. Some chronic cases can survive, although this requires intensive nursing and massive owner commitment. Some horses which survive chronic grass sickness can return to work

How do we diagnose EGS?

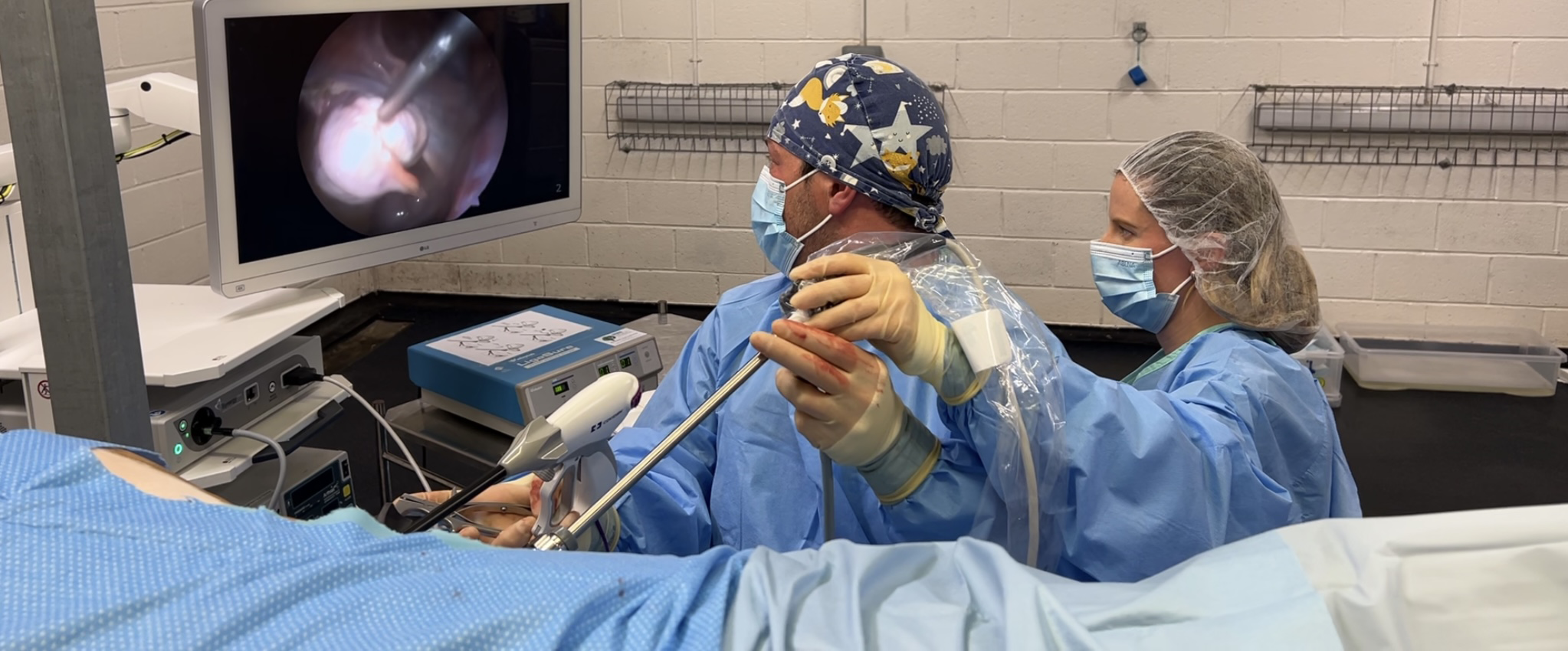

Diagnosis can be easy in some cases which show ‘classic’ signs however some cases need to be distinguished from other causes of colic, difficulty swallowing or weight loss. The only way to make a definite diagnosis is to examine a piece of small intestine which is collected during surgery, or after death. A nerve ganglia is also commonly examined after death. Characteristic changes in these tissues give us the diagnosis. There is no way currently to definitely diagnose EGS in a live horse without the need for surgery; therefore exploratory laparotomy (colic surgery) is often required to rule out other causes of colic.

How can we treat EGS?

Acute and subacute cases are generally considered incurable. Chronic cases can respond to supportive care and symptomatic treatment (treating the symptoms we see) Nutritional support is the most important factor and specific information regarding this can he acquired from the Hospital. Human contact, anti-inflammatory pain killers, regular grooming and coat care as well as hand walking and veterinary care are also required. Recovery will take several months and is very variable between individuals. Cases which are likely to survive tend to gain weight in the first few weeks and do not have extreme weakness, colic or marked dullness.

Prevention

If there has been a case on your premises or where your horse is kept, there is some general advice which can help to reduce the chance of another horse being affected. Please speak to your vet for the latest advice.

If there has been a case and if moving other horses will not cause too much stress, it is generally advised that they are moved to a different field or stabled. The difficulty is that when a field is safe to use again is almost impossible to determine.

Other things to do following a case are:

Avoid

- Soil disruption (pipe laying/construction work etc)

- Keeping domesticated birds on pasture

- Mechanical removal of droppings from pasture

- Over use of Ivermectin based wormers (this does not mean don’t worm! Please speak to your vet for individual advice)

- Stress: such as castration, exposure to new horses, breaking etc

- Sudden changes in feeding

- Excessive soil exposure such as over-grazing and poached fields

- Keeping horses over weight

Positive (to do)

- Co-graze with sheep and cattle

- Remove droppings by hand

- Give supplementary hay to reduce grass intake

- Stable horses for part of the day/night if there is a higher risk of disease – this particularly when there are more than ten consecutive days of dry weather with a temperature of 7-11 degrees C or if a case has occurred on the pasture